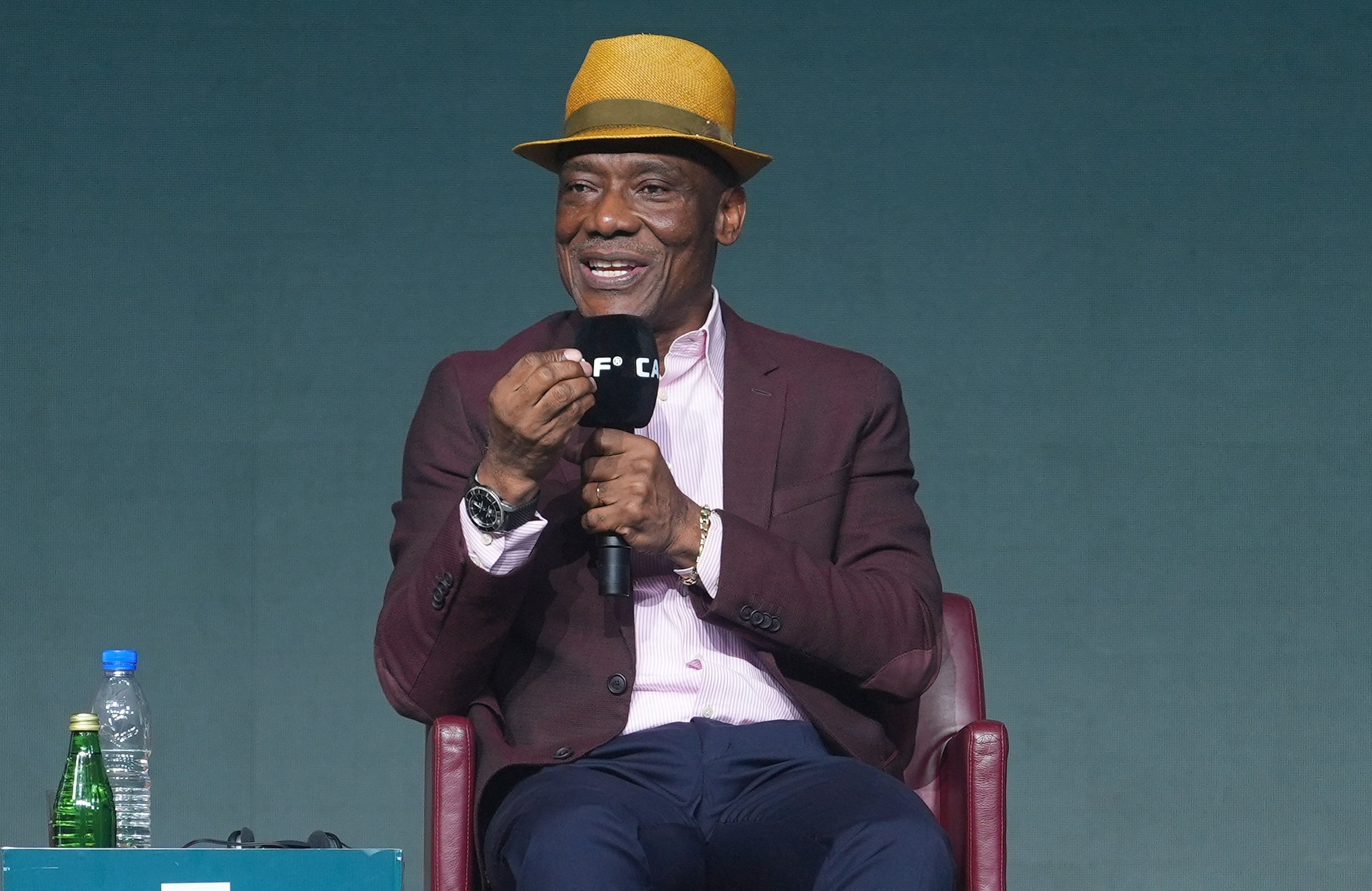

Joseph-Antoine Bell: The Goalkeeper Who Left His Mark on Morocco at AFCON 1988

- Joseph-Antoine Bell, legendary figure of the Indomitable Lions, was the cornerstone of Cameroon’s victory in Morocco in 1988

- His role as goalkeeper and leader embodied the mix of solidity, focus, and fair play that carried Cameroon to triumph

- As Morocco prepares to once again host the TotalEnergies CAF Africa Cup of Nations, the memory of Bell and his team inspire a new generation of African footballers

The last time Morocco hosted the TotalEnergies CAF Africa Cup of Nations was in 1988, when Cameroon—led by iconic figures such as Joseph-Antoine Bell and Roger Milla—claimed their second AFCON title. That victory was more than just a trophy: it confirmed the character, unity, and technical mastery that made that generation a symbol of African football.

Today, as Morocco gears up to host the TotalEnergies CAF AFCON again, the memory of that triumph lingers over every stand and every pitch. For Joseph-Antoine Bell, the emblematic goalkeeper of that team, this return to the Cherifian kingdom stirs both pride and memories of a demanding kind of football, where focus, fair play, and resilience dictated every match.

With 100 days to go until the TotalEnergies CAF AFCON 2025, the tournament stands both as a vibrant tribute to 1988 and as the opening of a new chapter, where African teams are ready to write their own legend, following in the footsteps of the Indomitable Lions.

CAFOnline.com: In March 1988, Morocco was preparing to host AFCON. What was your state of mind, knowing you had won the title in 1984 but lost it in 1986?

Joseph-Antoine Bell: Before the competition began, I was a bit detached from the event because I was playing in Marseille. At the time, there were no FIFA windows, so clubs weren’t required to release players. Since I had already won AFCON in 1984, I thought it wasn’t a big deal if I didn’t go.

But the coach, Claude Leroy, insisted. He told me: “I have a good team, if you come, we can win it.” At first, I didn’t take him seriously—I thought he just wanted to flatter me.

What really convinced me was an incident with Marseille. Bernard Tapie said it was up to Michel Hidalgo to decide on my release. Claude Leroy was waiting for a call from Hidalgo… which never came. I saw this as a form of disrespect, not toward Claude Leroy personally, but toward Cameroon. That motivated me to accept and go play AFCON.

Because of the calendar, I had to juggle between Marseille and Morocco: I missed Cameroon–Egypt, our first match, but then I played a marathon of 8 games in 13 days, between France and Morocco. Every match I played to win, and little by little, we realized we could take the title.

During that tournament, you were almost unbeatable: only one goal conceded. How do you explain such defensive solidity, despite all the travel between Marseille and Morocco?

The teams that go far are the ones that concede few goals. Claude Leroy knew that my presence would reassure my teammates and boost their confidence.

There’s also a simple logic: if you don’t concede, you only need to score one goal to win. Since we weren’t a high-scoring team, our chances of victory depended on a solid defense.

On top of that, I was Marseille’s captain—the first black goalkeeper to hold such a role in France. That sent a double message: I was not only reliable, but also a leader. This gave confidence to my team and even unsettled our opponents.

What distinguished Cameroon in 1988 from other African national teams?

If it were another field, people would have said Cameroon was “cheating”! (laughs) By the end of the century, when individual awards became common, you’d often see a Cameroonian ranked as the best goalkeeper in Africa, the second-best goalkeeper in Africa… and also the best striker in Africa.

We had quality across the board. And we had character. For example, in the semifinal against Morocco (0–1), at their home, we were not intimidated at all.

You see, when it comes to focus, there’s no secret: being excellent means ticking most of the boxes. To perform in any field, you need to meet all the demands. If you can’t maintain concentration, you’ll inevitably make mistakes. And someone who keeps making mistakes cannot be considered excellent.

It’s like a math teacher—you can’t say he has mastered mathematics if he can’t explain it. In that case, he isn’t really a math teacher. Excellence means being able to deliver. To be recognized as “good” means being unlike everyone else: technically sound, tactically intelligent, physically solid, mentally strong, and able to stay perfectly focused.

In short, Cameroon’s 1988 team had an exceptional squad: defensively strong and capable of scoring at key moments. That balance made the difference.

You faced Nigeria twice that tournament: once in the group stage (1–1) and again in the final (0–1). How would you describe the Cameroon–Nigeria rivalry at that time?

I almost have a personal history with this rivalry. At first, I’m not even sure Nigeria was aware of it, beyond being neighbours. But Cameroon was traumatized by Nigeria.

Before I was even in the national team, Cameroon’s greatest player, Mbappé Lépé, saw his career ruined after missing a penalty against Nigeria in Douala during the 1970 World Cup qualifiers. He never missed penalties… but that one scarred a whole nation.

Later, when I started with the national team, I realized how deeply this trauma was rooted. At the 1978 All-Africa Games in Algiers, we were drawn against Nigeria. I was young, fearless. But an older cousin asked me: “How will you handle Nigeria?” That’s when I understood what that match meant to Cameroonians. I played that Cameroon–Nigeria in Algiers. It ended 0–0. For me, it was fine; for Cameroon, it was already symbolic. From then on, our clubs began beating Nigerian sides.

In 1984, we beat Nigeria in the AFCON final. I remember a radio show with Roger Milla and me on one side, and Stephen Keshi on the other. Keshi, younger than us, proudly announced that his team had promised the trophy to Nigerians. That woke us up—we realized they weren’t coming to do us any favours. They scored first in the final, but we came back to win.

In 1988, once again we faced them. For them, it was revenge time. But we won again. The rivalry was now established, deep, and assumed. Later, in 1994, when Cameroon failed to qualify for AFCON in Tunisia, Emmanuel Amunike told me the Nigerians said: “This time, it’s our turn.” And they did win it. The Cameroon–Nigeria rivalry had become a concrete reality.

What do you feel today when you think back to the 1988 victory?

Every victory brings back good memories. The 1988 one I associate with team solidarity and mental strength. We had a connection between players and staff that made us confident we’d overcome any challenge.

But I also think of the sadness we caused Morocco. It was a huge disappointment for them: eliminated in the semifinals by Cameroon, then forced to watch the final at home without their team. The stadium supported Nigeria, but we still won.

We had just one Moroccan supporter that day: our bus driver! Looking back, it makes me smile, but it was a powerful moment.

How were you welcomed back in Yaoundé after that triumph?

It was a nationwide celebration. Cameroon was learning how to win. After 1984, after the 1982 World Cup, every victory was experienced as a major national moment. In 1988, the streets were packed, and the next day was declared a public holiday.

Thirty-seven years later, what would you like people to remember about Joseph-Antoine Bell, African champion in Morocco?

I’d like people to remember my fair play. That I was a goalkeeper who played with a smile. That I wanted to win at all costs but also thought about my opponents and their sadness after a defeat.

How do you feel seeing your native Cameroon return to Morocco 37 years after your victory?

This isn’t the first time we’ve won a tournament on African soil. In 1984, we won in Côte d’Ivoire, yet what followed didn’t go as planned—we even experienced one of the toughest AFCONs in our history.

I hope this time lessons will be learned and AFCON in Morocco will be prepared with seriousness and reflection. It’s not enough to say “we won in 1988”; we must draw inspiration from that victory in how we build the team, manage matches, and handle pressure.

In 2024, we went to Côte d’Ivoire saying “we won here in 1984” but didn’t actually learn from it. As a result, we failed.

So I hope this time, the team will truly take the lessons from 1988 and arrive in Morocco saying: “We’ve won here, we know how, and we’ve come back to shake things up.”

In a few days, we’ll be 100 days from AFCON 2025. What message would you send to African football fans?

Our national teams are becoming stronger and stronger. We’re going to Morocco, a country that is not just the host, but also one of the continent’s best, a World Cup semi-finalist.

But I want to stress one thing: fair play isn’t just for players. Supporters must also understand that football is meant to bring people together and create joy.

We can be rivals without being enemies. Without an opponent, there’s no football match. So, you must love your opponent, because he is just as important as you are.